The Anatomy Of An EdTech Ad

Part 3 of 3: The Hero

When I see an ad, I often ask myself, “Who is the hero of this ad? Is it the product, or is it the customer?” It's an abstract concept, but I use the heuristic of looking at the amount of real estate spent talking about the product or the target customer.

For example, Coursera uses two ads for the same product.

The first ad puts the course front and center—the name alone takes up most of the real estate. The second ad, however, shows a customer who took the course and the outcome they achieved—the focus is on the customer. Notice that the second ad even removes the 5-star rating, as it focuses on showing the customer they can be the “hero.”

Intentionally casting products or customers as the heroes of different ads in a campaign not only diversifies your ad portfolio but also helps you build an ad strategy tailored to your product-market fit along three dimensions.

Stage of funnel

Level of consideration

Vitamin vs. painkiller

As a reminder, this EdTech growth series is a collaboration between ETCH, your home for EdTech news and information, and my growth practice, Growth Fraction, where I partner with EdTech companies in leveling up their growth marketing and SEO. This includes scaling or driving efficiency in paid channels as well as launching new go-to-market strategies. You can book a free growth consultation here.

This issue is part three of breaking down the anatomy of an ad.

Part #1 Ad Texture: Captivate the audience enough to pause their scroll

Part #2 Emotional Resonance: Persuade the audience to stay a while

Part #3 (this issue). The Hero: Nudge the audience into taking an action

Stage of funnel

In the earliest stages of the marketing funnel, prospects are beginning to discover your brand and, to a lesser extent, learn about your product.

At this stage, forming an emotional connection with prospects can be more impactful than a direct focus on your product's features. Addressing a prospect's identity, aspirations, or challenges helps a prospect feel "seen," earning you the opportunity to show your product as the hero later in their decision journey.

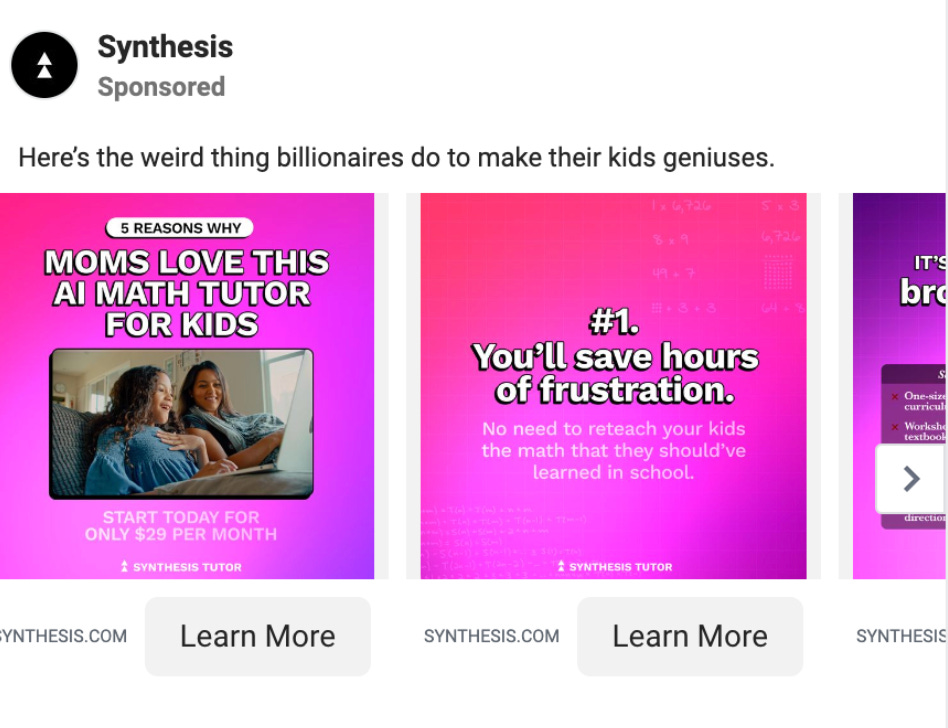

Synthesis does a great job in its advertising to help prospects feel seen. Its ads show moms as heroes and how they deserve the relief the Synthesis product can provide them. This strategy is even more notable when you consider that kids are the actual consumers of Synthesis’ product, yet the ad focuses on a mom's journey instead of highlighting the features their kids can access.

Synthesis is a newer brand in the early stages of building brand awareness. That's why I like its strategy of highlighting its customers as the hero. I also like how Synthesis balances showing the value a mom gets (e.g., reducing frustration) while also showing a happy child. What makes a parent feel more heroic than a happy child?

It's easy to imagine a Mom relating to the emotional sentiment of the ad above and engaging with it, but maybe not purchasing right away. As days or weeks go by, the Mom may remember the ad as they feel the “frustration” the ad spoke to.

This moment is the perfect time for Synthesis to shift the hero in their ads from customer to product, as their second ad below shows.

Notice how the same brand shows a different aesthetic when highlighting a product hero vs. a customer hero. When showing the customer as a hero in the first ad, Synthesis used bright colors and focused on eliciting emotion. For the second ad, Synthesis chooses a minimalistic aesthetic to focus on product features and potential blockers—for example, highlighting that the app is self-paced to nudge a parent who is unsure if it will fit their kid.

The takeaways here are two-fold:

You don’t need a consistent hero throughout the customer journey. Instead, you can cast the hero best suited to nudge the customer to the next step in the funnel. (Of course, this begs the question – “Where is a customer in their journey?” A question we will revisit in a later issue)

When brands have lower brand awareness, speaking to a customer's emotions and profiling them as the hero is a powerful strategy at the early funnel stages

Level Of Consideration

Another factor to consider when choosing heroes to feature in an ad is the level of consideration they give to purchasing a product. “Level of consideration,” a term used in the marketing industry, encompasses the amount of time and energy a prospect dedicates to evaluating the product's cost and its wide-ranging benefits. This includes the product's utility, potential emotional appeal, and alignment with their lifestyle.

With that in mind, the three factors that impact consideration of educational products are:

Price: Higher education, tutoring, and even some edutainment products can comprise a material share of someone’s annual budget. For instance, according to Sallie Mae, parents allocate about 45% of their income to cover their child's college tuition costs on average.

Personal significance: Education is often closely linked with a person's identity, influencing consumers to evaluate how it aligns with their sense of self.

“Free” or lower-priced alternatives: Many paid Edtech products have “free” or significantly lower-priced alternatives that seem similar to higher-priced ones. For example, you can get AI certified with an $800 nanodegree or a $3K certificate or take free AI courses directly from Google.

We can think of the above variables - higher pricing, personal significance, and the proliferation of free alternatives – increasing the level of consideration.

The higher the purchase consideration, the longer it takes a consumer to move from an ad impression to a product purchase. Moreover, the higher the consideration, the more critical it is to highlight the prospect as the hero rather than profile the “product” as the hero, even including customer hero concepts in later funnel stages.

Given the six-month time commitment, Coursera’s Data Analytics Certificate is an illustrative example of a product with high consideration. Ads for their Data Analytics Certificate show how they effectively use both the product and the prospect as the hero below.

The first ad profiles the customer as the hero, which can be a stronger performer in the early funnel when you are trying to gain consideration by connecting emotionally.

Conversely, the second ad profiles the product as the hero by emphasizing the course name and reviews. As we discussed in the prior section, that product-centric ad style can work well in the later stages of the funnel when the customer is closer to a purchase.

However, Coursera is different from Synthesis because it is a higher-consideration purchase; this course's price point and time commitment are significantly higher.

As a result, Coursera has to invest more upfront in customer hero ads, as there is a higher bar to clear to connect with and convince customer prospects. Coursera even creates multiple customer heroes, as shown below.

As another example, let’s look at Grammarly, which some may consider a commodity given native grammar check functionality in document editors and “free” alternatives like Hemingway. This fact makes it more imperative for Grammarly to go beyond highlighting features of their product and show the customer as the hero. This is likely why many Grammarly ads feature customer heroes, often quite literally so, as shown below.

In fact, I loved this ad so much that it made me renew my lapsed Grammarly subscription.

Vitamin vs. painkiller

The final variable in building your customer-as-hero process is whether your product is a vitamin or painkiller - a “nice to have” or “need to have.”

The more that customers view a product as essential, the easier it is to highlight it as the hero in advertising. In contrast, the closer a product is to a luxury, the more critical it is to portray the customer as the hero, illustrating how they can elevate their life.

I found something interesting as I looked for examples of “vitamin” and “painkiller” products and their respective ads.

The MIT ads below are for a deep learning course, which many would consider a vitamin – a “nice to have.” Yet all their Meta ads focus on their product without talking about the prospect and how they can achieve a heroic outcome.

Contrast this with the MIT course ads below for systems thinking and systems engineering.

The systems class ads focus on the prospect, unlike the product-centric deep learning class ads. Both categories of courses cost north of $1,000, and one could argue they are both “vitamin” products. So, with so much in common, why is there a difference in ad strategy?

I suspect the difference is a function of the intended audience. For many in tech, AI is THE topic of conversation, and leveling up your AI skills might be the difference that gets you promoted. While helpful, systems thinking might be seen as more of a “nice to have” for prospective students and their employers.

This could explain why the AI courses can “get away” with just showing the product, while the Systems Engineering course has to spend more time making the customer the hero to get them to purchase the course.

The landing pages below further reinforce the product vs. customer focus. The AI landing pages focus on lead capture, while the Systems Engineering landing pages focus on more human customer hero elements, including a video. The systems engineering page aims to connect with the customer, while the AI landing page aims to push the customer to a transaction.

Implications

Whether the product or the customer takes center stage in advertising is not merely a matter of creativity. It's a strategic decision that EdTech marketers need to make while considering three core factors:

Stage of Funnel: Showcasing your brand or product before putting the spotlight on your product ensures an audience feels an emotional resonance with it.

High vs. low consideration: Overcoming higher levels of consideration requires a deeper connection with prospects to cut through the many purchase blockers.

Vitamin vs. Painkiller: Essential products naturally lend themselves to being featured as heroes with clear and often immediate value. In comparison, luxury products do well by starting with a narrative that places the customer at the center of a transformative experience.

What’s coming next?

Now that we have covered the anatomy of ads, our next issue will discuss product-market-channel fit.

I love this topic because, despite all the talk about product-market fit (PMF), go-to-market strategies often succeed or fail based on the unit economics of their distribution channels.

As a thought exercise, consider which factor more heavily influences the growth of your business—the market size for your product or the marginal cost to acquire a new customer in your main channel.