“What are the jobs to be done for our customers?” This is a standard opening salvo of a product marketing brainstorming session. The “Jobs To Be Done” (JTBD) terminology references a framework that identifies the drivers of consumer behavior. With an understanding of these drivers, a marketer can position the product as a solution to the job.

However, the JTBD is often misapplied by focusing on functional jobs and missing the fundamental driving force of acquiring customers – emotion.

When applied correctly, the JTBD framework, shown above, identifies emotional drivers and divides them into personal and social dimensions.

For example, an EdTech product could solve a functional job (e.g., getting a better career). However, the more powerful motivator for the consumer is more likely to be an emotional job (e.g., feeling secure).

Interestingly, this is confirmed by science, as brain scans show that people use emotions over information when evaluating a brand.

That might be why this New Balance ad does not talk about how comfortably you can run in their shoes.

As a reminder, this EdTech growth series is a collaboration between ETCH, your home for EdTech news and information, and my growth practice, Growth Fraction, where I partner with EdTech companies in leveling up their marketing — with an emphasis on performance marketing and SEO. To learn more, you can book time with me here.

This issue is part two of three in breaking down the anatomy of an ad.

Part #1 (last issue). Ad Texture: Captivate the audience enough to pause their scroll

Part #2 (this issue). Emotional Resonance: Persuade the audience to stay a while

Part #3 (next issue). The Hero: Nudge the audience into taking an action

Emotion over Function

Starting with emotion over function can create powerful ads that speak to an audience. Someone thumbing through an endless scroll often sees “functional” messages as digital clutter with transactional speak.

However, emotional motivators, like building confidence, have the power to grab attention. Remember, your ad is not simply competing with education companies. You are competing against the emotional pull of a Vice documentary or one of 18 million cat videos.

Here are a few examples of the difference between functional messages and emotional motivators in the EdTech space.

Starting with emotion (e.g., confidence, community) is a powerful way of connecting with a customer and driving purchase consideration. In this context, a prospect’s main question is, “Will this purchase fulfill my emotional need?”.

Conversely, emphasizing function (e.g., career mobility) prompts a customer to question the value. For example, when your pitch is “We help you level up in your career,” prospects’ often ask two questions:

Can I get this outcome at a cheaper price?

Will I really achieve this outcome?

In short, focusing on function invites more questions. Appealing to emotion invites a purchase.

Emotions that drive EdTech purchases

Borrowing from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we can adapt a generalized framework for common emotions that drive EdTech buyer decisions. These emotions serve to clarify the motivator(s) your ad is speaking to, not to imply that some are more valuable than others. As you consider using emotions in your own ads, make sure your usage is deliberate and consistent with your go-to-market strategy.

One other thing to think about when appealing to your audience’s emotions is the natural tradeoff between the intensity of the emotion and the addressable market, particularly when you are generating demand (e.g., Facebook) vs. capturing intent (e.g., Google).

Fear and Necessity (lower pyramid): Ads targeting these emotions tend to be direct and often narrower in their customer target.

Aspiration, Identity, and Delight (upper pyramid): Ads targeting these emotions tend to ask questions and look to broaden the customer base.

Let’s take the following two ads for language learning products to illustrate the difference in targeting fear vs. delight.

Consider that both products have the same functional job – to improve language skills. But the Preply ad speaks more to the emotional blocker (i.e., fear) of acquiring a skill. Meanwhile, the Duolingo ad focuses on a broader audience looking for joy and presents Duolingo as a part of the solution.

That is not to say that one of Duolingo or Preply’s ads is “better” than the other. These emotional framing differences show how brands with similar products can target different customer segments and emotions. The deliberate alignment of customer segments with specific emotional motivators underscores a brand’s understanding that activating different emotions for a broad audience is critical to a go-to-market strategy.

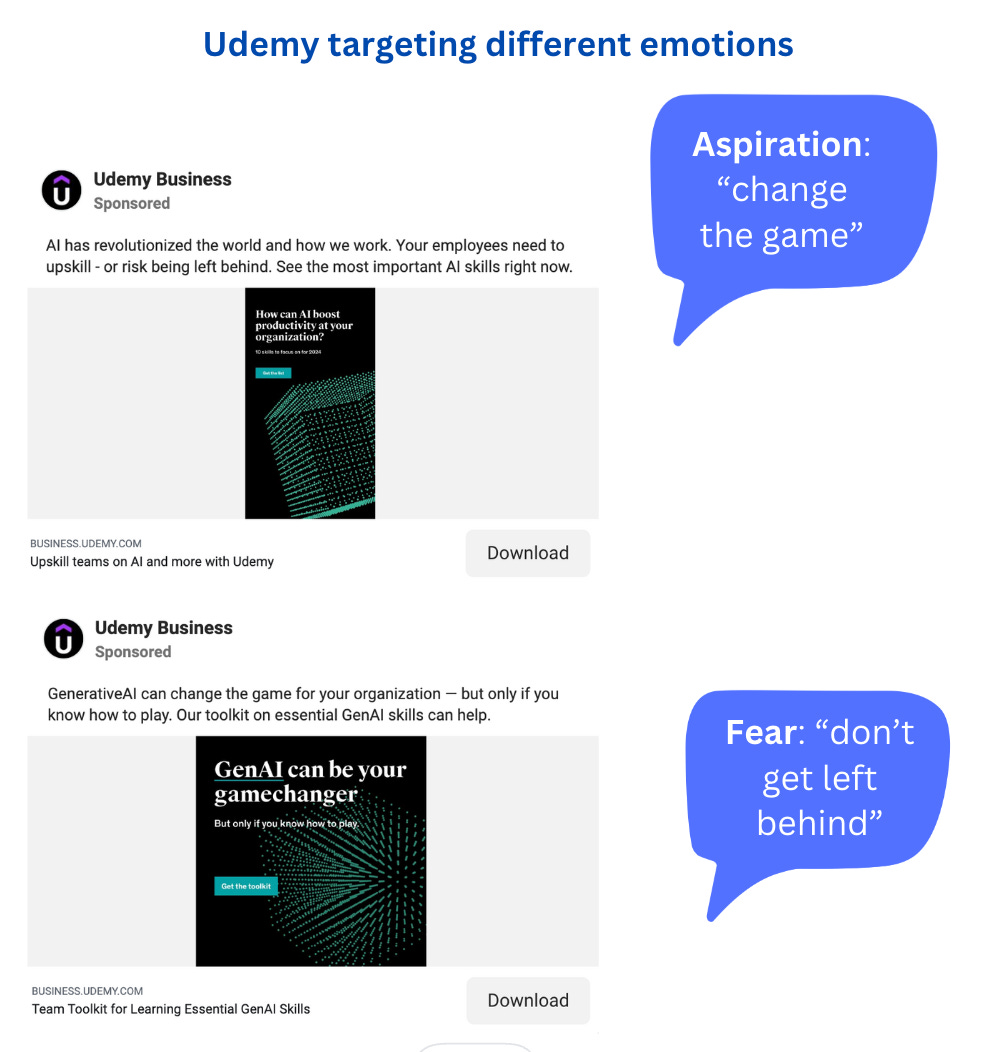

To show one more example, the ad below highlights Udemy’s efforts to show their GenAI courses as both aspirational (e.g., unlocking a new level) and as a way to quell the fear of being unemployable.

Notably, fear often supersedes aspiration, as loss aversion can be a stronger motivator than the desire for gains. This is partly why we see fear messaging so much in digital media. It is a catalyst, and many brands are willing to bear the brand risk of tapping into a “negative” emotion they know drives purchases.

Implications

Speaking to different emotional needs in ads affects how you sell to customers and differentiate from the competition. In the above examples, I’ve tried to outline how EdTech companies use emotion in their advertisements. Below, I’d like to give you a simple framework for thinking about how and where you might consider using different emotions in your own go-to-market strategies.

Additionally, understand that certain emotions fit particular use cases. If the goal of your ad is to convert a user today, designing an ad around “necessity” might work well. If your ad is the first step in a long sales cycle, perhaps “delight” might work better.

The most important thing to remember about appealing to emotion is that you have to try it. Every ad you make will land differently with customers than you expect - which means you will have to test many iterations to find the right balance of conversion rate, differentiation, and brand perception. A willingness to experiment is a critical component of building an effective go-to-market strategy and something we will go into even deeper detail on in next week’s piece.

What’s coming next?

Our next issue will cover the “hero” of an ad – and how that nudges a customer to act. To continue to get updates in this series, subscribe below.